Jeff Wall, The Thinker, 1986, transparency in lightbox, 239 x 216 cm Collection Lothar Schirmer, Munich Courtesy of the artist. © Jeff Wall.

Ask here for available works by Jeff Wall – click here.

About the Artist

Over the last three decades Jeff Wall has redefined the photographic image in art. His stunning large-scale photographs exude the dramatic power of history painting with utterly contemporary subject matter (everyday scenes from modern life) and materials (colour transparencies in light boxes). Each of his photographic tableaux is meticulously constructed — carefully staged, precisely lit and, since the late 1980s, digitally adjusted — in a process that the artist often compares to cinematography.

Wall has sometimes referred to his photographs as ‘near documentaries’ because they frequently come from scenes he has witnessed in passing and recomposed later. But he also disavows any claims to photographic truth, constructing many of his pictures around works of art and literature, such as the writings of Franz Kafka, Ralph Ellison and Yukio Mishima and the paintings of Hokusai, Delacroix and Caravaggio.

Wall was born 1946 and raised in Vancouver, Canada. While studying art history at the University of British Columbia in the 1960s, he became interested in Vancouver’s experimental art scene and taught himself photography, seeing it as the best tool for expressing his conceptual ideas. He received his Bachelor of Arts degree in 1968, and his Master of Arts degree from the same university in 1970. From 1970 to 1973 he did postgraduate research at the Courtauld Institute, University of London. In 1974 he accepted his first teaching position, at Nova Scotia College of Art and Design in Halifax, subsequently teaching at Simon Fraser University, Vancouver, 1976-87, and since 1987 at the University of British Columbia. Early group exhibitions include 1969 shows at the Seattle Art Museum, Washington, and Vancouver Art Gallery, andNew Multiple Artat the Whitechapel Art Gallery, London in 1970. His first one-man show was held at Nova Gallery, Vancouver in 1978. Other solo exhibitions have been held at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London in 1984, and the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, 1995, which toured in 1995-6 to the Jeu de Paume, Paris, the Helsinki Museum of Contemporary Art, and the Whitechapel Art Gallery, London.

About this work

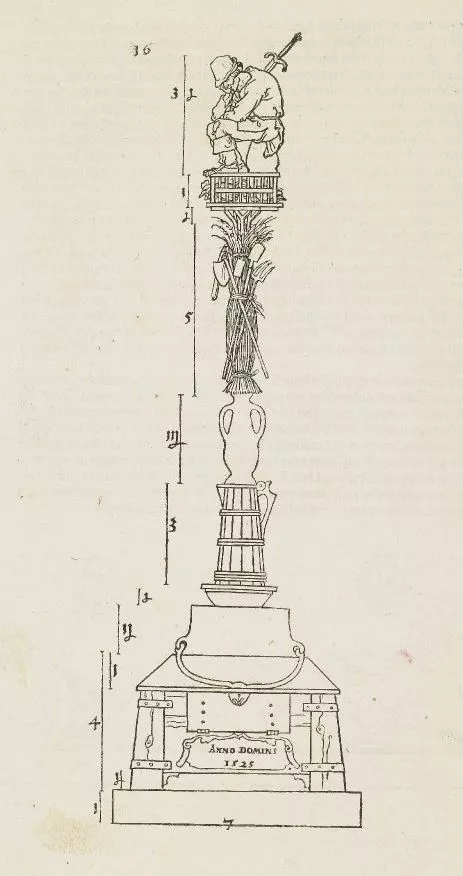

The title of The Thinker (1986)itself of course is a reference to Rodin. One of Walls reinterpretations of a famous work from art history that he pictures render in a manner that seems so timelessly contemporary. With his Thinker, Wall transfers the figure in the typical Thinker pose to a contemporary urban setting and introduces the “grotesque” element of a knife in the protagonist’s back, which in turn alludes to Albrecht Dürer’s Peasants’ Column from 1525, a proposal for a monument that was never built. Wall describes the peasant who sits atop the column, the sword in his back a symbol of betrayal and defeat, as ‘mourning for the fate of his and his class’s hopes for emancipations’.

Literature: Albrecht Dürer, Peasants’ Column (24) book 3, Plate 16 in ‘Underweysung der messung’, (A course on the Art of Measurement), Nürnberg 1525. The British Museum, London. Click here!

Jeff Wall: “Picture for a Women”, 1979, Silver dye bleach transparency in light box, Collection of the artist. Copyright © 1979 Jeff Wall

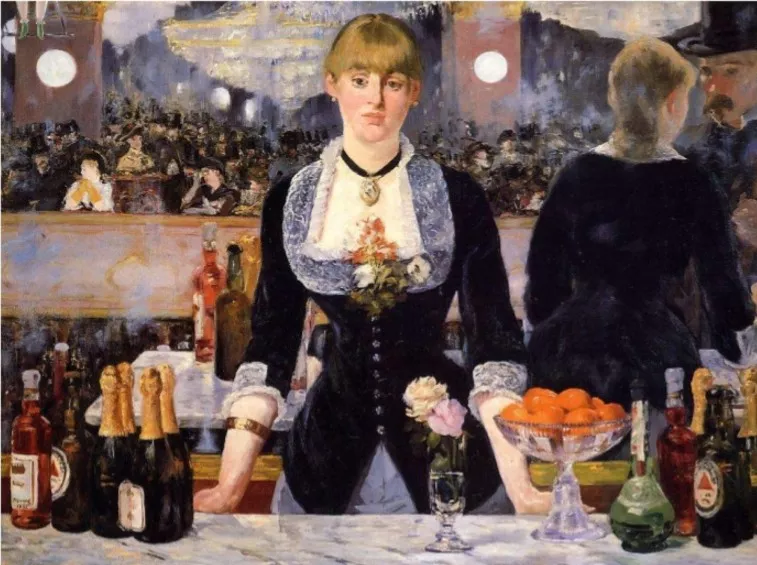

Jeff Wall’sPicture for Women(1979) marks the transition of photography as contemporary art form from the printed page to the gallery wall. In the photograph a woman looks outward, as if at the viewer; a camera occupies the centre of the image; the photographer stands on the right. Modeled on Édouard Manet’s paintingUn Bar aux Folies-Bergère,Picture for Womenis an ambitious attempt to relate the artistic and spectatorial demands of the late 1970s to modernist pictorial art.

Edouard Manet: ” Un Bar des Folies-Bergère “, 1881, Huile sur toile, 96,2 x 130 cm, © Coutauld Institue Galleries, Londres

The photo offers an account of Wall’s move from a Conceptual approach to a reengagement with the idea of a singular (rather than serial) picture. Contrasting Wall’s idea of the photograph as a tableau or a ‘picture’ with the works of the Pictures Generation – including Richard Prince, Cindy Sherman and Sherrie Levine – you can argue that Picture for Womenis inseparable from the modern fate of the picture in general. From here Wall’s image is placed in a broader context of photographic art, including the work of Manual Alvarez Bravo, László Moholy-Nagy, Edward Weston, Lee Friedlander, Victor Burgin and John Stezaker.

Jeff Wall,A View from an Apartment, 2004-05, transparency on lightbox, 1670 x 2440 mm © Jeff Wall

The Destroyed Room, from 1978, is one of Canadian artist Jeff Wall’s first and most iconic photographs. The work consists of a large photograph printed as a cibachrome transparency within a fluorescent lightbox. Around 5 by 8 feet in size, the work is both vivid and imposing. Offering a stark view of a seemingly ravaged space the image forces the viewer to confront the destruction of items found within the typically intimate space of a bedroom. Clothes are spilling out of the drawers of a wooden dresser, a bed is turned on its side with its pale green mattress slashed, possessions such as clothing and accessories are strewn about the floor, and large pieces of the red wall are missing, exposing the pink insulation underneath.

With this photograph, Wall first began making overt references to some of the most famous examples of classical painting from the 19thcentury. InThe Destroyed Room, the large-scale oil painting titledThe Death of Sardanapalus, painted by Eugene Delacroix in 1827, is the source of inspiration. The painting depicts an Assyrian king, Sardanapalus, casually reclined on an enormous red bed as he watches his most prized possessions – living and non-living – being destroyed. The slaughter of concubines and servants, horses and dogs, was prompted by an invading enemy. Rather than surrender, the king decides to end his life, but not before ensuring that his belongings would never be enjoyed by anyone else. Many elements in Wall’s photograph echo the visual details of Delacroix’s painting, including the diagonal composition of objects from the top left corner to the bottom right corner of the frame, the bright pink and red hues that invoke the nudity of the female concubines and the blood of the violent acts, and the likely evidence of physical struggle.

WhileThe Death of Sardanapalusdepicts an act of violence as it occurs, Wall shows an aftermath. Whereas the painting shows the luxurious space of a male ruler, the photograph seems to show a woman’s small living space. Wall’s work is devoid of people, though, leaving the viewer to imagine who might have occupied the space and why the room became destroyed. However, Wall has purposely left remnants of the staging process of the scene in the final image, making the fabrication of the room obvious. Upon scrutiny, it’s possible to see that at least one of the room’s three walls is only barely supported with wooden beams. In an article entitled “The Luminist” in The New York Times Magazine on the occasion of Wall’s retrospective exhibition in 2007, Arthur Lubow remarks how Wall has admitted that he enjoys the process of artistry just as much as the final product.InThe Destroyed Room, Wall not only hints at the creative process, but also engages with the questions raised by Conceptual artists of the time. Throughout the 1970s, photography was increasingly used by artists to call attention to the fabricated quality of art and the performance of subject matter and ideas within artworks. For these artists, including Wall, photography was freed from its role of visually capturing the real world. By creating a large-scale, fictional image that recalls the grandeur and narrative of classical painting, Wall challenges the documentary role that photography often plays. But by mounting the image in a lightbox, his work also resembles imagery from cinema or advertising found in popular, contemporary culture. Thus, Wall simultaneously highlights the real and imagined in art, raising photography to the level of fine art typically held by painting over the ages while referencing elements of the modern day.

Jeff Wall: “A sudden Gust of Wind”, 1993 © Jeff Wall

Wall’sA Sudden Gust of Wind (after Hokusai), reinterprets the scene in a woodcut print by Japanese printmaker and painter Katsushika Hokusai. Part of the larger portfolio calledThe Thirty-six Views of Fuji, Hokusai’s original image,Travelers Caught in a Sudden Breeze at Ejiri(c. 1832), depicts seven individuals caught off-guard in the wind at different points along a narrow path. The path weaves its way through lush green and blue fields, with the majestic Mount Fuji resting in the background. In Wall’s photographic work, the individuals caught in the wind in the foreground mimic the poses of the travelers in the earlier woodcut, but otherwise evoke a time and place far removed from the calm Japanese landscape.

Wall’s large-scale image is actually made up of multiple photographs taken over the course of several months, then later digitally combined to create a final collaged composition. Four figures appear caught mid-movement, situated at different points in front of a canal of water cutting through an otherwise barren field. We see mostly flat lands stretch into the background, with a row of power lines receding on the right side of the image, suggesting a more industrialized location than the site in the original woodcut. A figure at the far left of the group crouches slightly, head obscured by a displaced scarf and hand holding a red folder that is losing its paper contents in the wind in a diagonal direction up and over the group to the right. Dressed for the outdoors in rubber boots and hat, another figure in the center bends with his back against the wind, clutching his jacket and walking stick. To his immediate right, the other center figure (dressed more formally, in buttoned shirt and tie) desperately looks upwards, arms outstretched and torso turned, as if ruefully watching the papers disappear into the wind. Finally, a figure at the far right crouches down closer to the water in the canal, holding on to his hat lest it escape. To the left are two tall, thin trees bending in the wind and nearly touching the top of the frame, their leaves blowing off and mixing with other papers scattered in the air. Taken together, the scene appears to be a random moment frozen in time, even when the elements seem incongruous. As arranged, these visual details beg more questions than they answer: the viewer is caught mid-story, unaware of why these people are gathered in this empty, dull space, or how this scene relates to that of Hokusai’s travelers.

Katsushika Hokusai (Japan, Tokyo (Edo) 1760–1849 Tokyo (Edo)) „Ejiri in Suruga Province (jap. 富嶽三十六景, Sunshū Ejiri)“, ca. 1830–32, aus der Serie “36 Ansichten des Berges Fuji” (Fugaku sanjūrokkei), Holzschnitt, Tinte und Farbe auf Papier, 25.4 x 37.1 cm © The Metropolitain Museum of Arts, New York, 1000 Fifth Avenue

Katsushika Hokusai (Japan, Tokyo (Edo) 1760–1849 Tokyo (Edo)) „Ejiri in Suruga Province (jap. 富嶽三十六景, Sunshū Ejiri)“, ca. 1830–32, aus der Serie “36 Ansichten des Berges Fuji” (Fugaku sanjūrokkei), Holzschnitt, Tinte und Farbe auf Papier, 25.4 x 37.1 cm © The Metropolitain Museum of Arts, New York, 1000 Fifth Avenue

Although this work continues techniques and themes first explored in Wall’s earlier photographs, it adds new layers to the broader investigation of photography’s role in both portraying reality and creating fictional narratives. This is also a large transparency displayed in a lightbox, with the light source coming from behind the image rather than spotlighting it from the front. The artist’s use of these big lightboxes to display photographs has often been discussed in reference to Wall’s interest in film, as the cinematic image is obscured until seen against a bright light. Here, too, just as the gaps between individual frames of film are hidden when the reel of film is in motion, Wall also attempts to mask the gaps that took place in time between the original photographs and the traces of their separate frames when combined all together in the final composition. In this way, Wall blurs the line between reality and fiction. On the one hand, the photograph displays real people caught in a real gust of wind. But on the other hand, it also displays an imagined scene that never existed in reality as it is presented to the viewer. As such, the viewer is left to wonder about what they are actually seeing. Wall may find his inspiration in the examination of influential works from earlier artists, but he reworks these compositions in ways that challenge the assumed narratives affiliated with certain times, places, and people, as well as the assumed uses of particular visual media.

Jeff Wall, Insomnia, 1994, Transparency in lightbox, 172,2 x 213,5 cm © Jeff Wall

InInsomniawe see an old gas stove against the left wall. Opposite to this on the right wall is a fridge/freezer. Against the rear wall we see avocado green kitchen cupboards. Some of the cupboard doors stand ajar. In the middle of the kitchen floor is a small table with two chairs beside it. Under the table lies a man. These are the cold, hard facts of the image which is known as the denotation.

But the denotation only tells us what is there. It doesn’t describe or allude to any emotion or meaning. This is where connotation comes into play. For instance, we know that avocado green was a very popular colour during the 1960’s. This conveys a sense of age to me and if we look at the gas stove, we can see that this too is a very old model. The lino on the kitchen floor has definitely seen better days as well. The stark light in the kitchen together with the cold green of the cupboards convey a sense of sterility to the image. This kitchen does not conjure up any sense of it being the‘the hearth and home’. It does not convey warmth and security at all.

The half open cupboard doors and the scrunched up brown paper on top of the fridge are indicative of a unsuccessful search that has taken place in the kitchen. Had the search been successful, the doors would most likely have been closed. Further evidence of a search is the awkward positioning of the two chairs in the kitchen. Were they moved to their current positions to aid in the search, or were they shifted to make space for the man below the table? Why is he lying on the cold floor, one has to wonder? Here we can attempt to delve into some psychoanalysis by means of research into symbols. In his unpublished work,Symbolism of Place, John Fraim of The GreatHouse Company makes the following comments on the symbolism of the house:

The symbolism of the house is associated with enclosed and protected space similar to the mother’s womb. In fact it is the first place in each person’s life. As an enclosed space it serves to shelter and protect from the outside world. … each house symbolizes that place of our earliest years and the nurturing cradle of those years. … A house or home can also be viewed as simply a place where we can express a private and unguarded self in an increasingly public world. … houses symbolize the lives of their inhabitants. … (It) reflects the psychology and personality of its inhabitant. (John Fraim inSymbolism of Place).

Indeed one can see from his body stance and gesture, it is clear that the man has assumed a slight foetal position and is seeking protection (under the table and within the confines of a small room). The man under the table serves as the punctum to this image. His placement is totally unexpected. The fact that he is lying on the floor alludes to his mental state. Something is obviously worrying him a great deal. He has a disturbed look about him.

Freud goes even further in hisA General Introduction to Psychoanalysisand states that:

We already know theroomas a symbol. The representation may be extended in that the windows, entrances and exits of the room take on the meaning of the body openings. Whether the room isopenorclosed is a part of this symbolism, and the key that opens it is an unmistakable male symbol. (Chapter X: Symbolism in the Dream)

Now I’m not sure that I would agree with Freud. I have never studied Freud, but the little I have gleaned over the years is that his ideas all have sexual connotations, some very far fetched in my opinion. The idea that open kitchen cupboard doors representing female organs seems to be quite the stretch in my humble opinion! No doubt one can really get involved in psychoanalysis if the expertise is there.

Jeff Wall is known for creating his photographs of moments or instances that he has witnessed after the fact. Wall’s image is created in the Renaissance style of the old master painters. Themise-en-scèneof the photograph is well thought out from the set design (the 1960’s kitchen) to the lighting (stark bright light) to the space (rather cramped) to composition (the use of diagonal lines to lead our eye all around the frame, the vertical and horizontal lines to provide some solidity to the image and the light and shadow in which the man is lying) down to the costume that the man is wearing.

‘He plays with the notion that implicit in every photograph is the sense of what happened before the moment depicted and what may happen after’(National Gallery of Canada). This statement sums up the crux of Wall’s intent with his images, for when we look at this image we are left wondering what caused this man to end up on the floor in such a state and what is going to happen to him. We, the viewers, are left to our own belief system and culture to complete the narrative. (Sharon Boothroyd).

Jeff Wall: “Untangling”, 1994, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Australia, © 1994 Jeff Wall

Untangling fuses the conventions of cinema with the authority of grand painting. This large backlit cibachrome transparency shows a complex and seemingly chaotic environment in which a huge knot of hemp rope lies across a garage floor. In the foreground a mechanic is shown seated on a pile of rubber tubing, contemplating the ropes as if beginning to untangle them. His troubled features contrast greatly with those of the younger man browsing motors at the rear of the shop.

Art can become a Therapy, the powerful and restorative benefits of art in our everyday lives can be divided in seven functions: remembering, hope, sorrow, rebalancing, self-understanding, growth and appreciation.

‘Like other tools, art has the power to extend our capacities beyond those that nature has originally endowed us with. Art compensates us for certain inborn weaknesses, in this case of the mind rather than the body, weaknesses that we can refer to as psychological frailties. Art (a category that includes works of design, architecture and craft) is a therapeutic medium that can help guide, exhort and console its viewers, enabling them to become better versions of themselves.

Jeff Wall, Milk 1984, Transparency in lightbox 1870 x 2290 mm, Cinematographic photograph, Collection FRAC Champagne–Ardenne, Reims © The artist

Milk is another depiction of a socially charged subject. ‘Suffering and dispossession remain at the centre of social experience’, Wall has commented. The explosive burst of liquid is emblematic of the man’s state of mind, but what might have provoked such extreme emotion is not revealed, a state of ambiguity that ensures the work cannot be understood as moral commentary. The process of reconstructing an event allows Wall the freedom to reinvent the composition. He often relocates the action to a different setting, a place chosen for its formal or pictorial qualities, as is the case here. The grid-like order of the brick wall background, and strong vertical bands that stripe the left side of the image contrast sharply with the tension in the man’s arms and the uncontrolled arc of milk.

Jeff Wall, The Storyteller, 1986, Silver dye bleach transparency in light box, Image: 229 x 437 cm (90 3/16 x 172 1/16 in.) © Jeff Wall

Wall’s staged tableaux straddle the worlds of the museum and the street. The scale and ambition of his pictures-scenes of everyday life shot through with larger intimations of political struggle-equally evoke the Salon paintings of nineteenth-century French painters such as Gustave Courbet and Édouard Manet and the advertising light boxes seen at airport terminals and bus stops. The combination is not as strange as it seems, however, in that these earlier artists regularly shocked viewers by chronicling the social transformations and class conflicts of their own historical moment in a manner deemed unworthy of serious art. References to their canvases abound in The Storyteller, from the trio of urban castaways echoing the figures in Manet’s Déjeuner sur l’Herbe to the steeply pitched, spatially ambiguous landscape that recalls Courbet’s Young Women from the Village. Yet these allusions are never gratuitous: Manet himself scandalized the public by having the roguish Parisian pleasure-seekers of his contemporary pastoral mimic the poses of Giorgione’s revered Concert Champêtre.

Set in a leftover sliver of land off a highway in Vancouver, where the artist lives, The Storyteller shows the liminal space where past meets future, crisscrossed by power lines and illuminated from within by the electric light that permeates our world of spectacle, consumption, and waste. Yet the work is ultimately hopeful, holding in suspension the potential for cultural traditions to survive and contest historical amnesia, the homogenizing effects of the media, and the empty promises of technological progress. In creating a space that is both irrevocably fragmented yet retains the possibility for coherence in the mind of the viewer, Wall’s picture is, in its largest sense, a statement about the meaning and function of art itself.

Jeff Wall, Mimic 1982, Transparency in lightbox 1980 x 2286 mm, Cinematographic photograph, Courtesy of the Ydessa Hendeles Art Foundation, Toronto © The artist

The large colour-print format that Wall favours requires a camera that is ill-suited to capturing fleeting moments, yet he wanted to explore the documentary style of street photography practiced by a number of photographers, such as Robert Frank or Garry Winogrand. Wall’s solution was to restage such moments, preserving a sense of immediacy by using non-professional actors in real settings. He calls these constructed images ‘cinematographic photographs’. In Mimic, the white man’s ‘slant-eyes’ gesture recreates a scene of racial abuse that Wall witnessed on a Vancouver street.

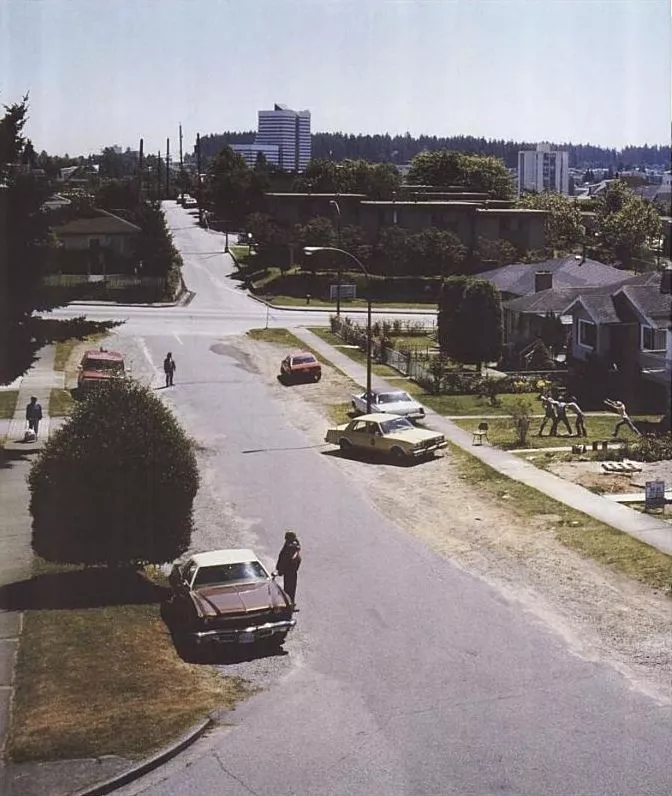

Jeff Wall: “Eviction Struggle”, 1988 / 2004 © Jeff Wall

The scene does not look realistic or natural, it is a staged scene as we know it from theatre and paintings. Especially in old historical paintings there are conventional gestures to express deep and violent passions reaching to the abyss of what can not be expressed. The german theorist of art Aby Warburg called them the formula of pathos. The gestures of the persons in the scene quote some of this formulas, for instance the man between the policemen is a rough quote of the Laokoon in the famous classical sculpture. The hold up arms of the woman is a quote of the gesture of Maria Magdalena on pictures of the crucifixion of Jesus Christ. But the reason of these quotes is not to reanimate these old passions, they are allusions to what has disappeared from our life. That shows us the stiff and exaggerated performance of these gestures, reminding us of bad overacting actors may be in a daily soap. Once more you can find here the in between of a remembrance of absent passions and their funny returning in the attitudes of every day life.

In “Eviction struggle” there seem to be two different perspectives. One from the outside, the right sight and from above running along the road, the other from down below, from the ground of the street running through the scene up to the landscape of the suburb. In an exhibition of Jeff Wall people are always running here and there to find out the right perspective. Actually there is no one, there is no safe position for the onlooker. He gets involved into the picture, get’s evicted from his own position and has to fight his own eviction struggle within and between the elements of the picture.

Jeff Wall: After “Invisible Man” by Ralph Ellison, the Prologue, 2000. Silver dye bleach transparency; aluminum light box, 5 ft. 8 1/2 in. x 8 ft. 2 3/4 in. (174 x 250.8 cm) MoMa, New York

Ralph Ellison’s 1952 novelInvisible Mancentres on a black man who, during a street riot, falls into a forgotten room in the cellar of a large apartment building in New York and decides to stay there, living hidden away. The novel begins with a description of the protagonist’s subterranean home, emphasising the ceiling covered with 1,369 illegally connected light bulbs. There is a parallel between the place of light in the novel and Wall’s own photographic practice. Ellison’s character declares: ‘Without light I am not only invisible, but formless as well.’ Wall’s use of a light source behind his pictures is a way of bringing his own ‘invisible’ subjects to the fore, so giving form to the overlooked in society.

Ralph Ellison’s 1952 novelInvisible Man, as the title of the photograph suggests, a scene from the prologue:

I sat on the chair’s edge in a soaking sweat, as though each of my 1,369 bulbs had every one become a klieg light in an individual setting for a third degree with Ras and Rinehart in charge.

The invisble man continues:

Perhaps you’ll think it strange that an invisible man should need light, desire light, love light. But maybe it is exactly because Iaminvisible. Light confirms my reality, gives birth to my form. A beautiful girl once told me of a recurring nightmare in which she lay in the center of a large dark room and felt her face expand until it filled the whole room, becoming a formless mass while her eyes ran in bilious jelly up the chimney. And so it is with me. Without light I am not only invisible, but formless as well; and to be unaware of one’s form is to live a death. I myself, after existing some twenty years, did not become alive until I discovered my invisibility.

Jeff Wall: Parent Child, 2018, Inkjet print, 87 13/16 x 99 13/16 in. (223 x 253.5 cm), © Jeff Wall

Parent child (2018) offers another sunny summer day, this time the scene is of a sidewalk in a suburban shopping district. A man gazes down at a little girl who has decided – for reasons of her own – to lie down on the presumably warm, clean and inviting sidewalk. Neither she nor her guardian shows any signs of frustration or impatience. Parent child has the relation to street photography that Wall has developed over the past decades; a contemplation of its effects by means of pictorial construction or reconstruction, a mode he calls ‘near documentary’.

The theme of self-absorption, or the failure to connect, extends to works featuring children in dreamlike states. In “Parent child,” a little girl is curled up on a stretch of sidewalk, ignoring her father’s pleading stare. Her little act of toddler rebellion brings a strange sense of stasis and endurance to the foreground of the picture, which in the background looks like a typical street photograph with passers-by caught in mid-stride. This photograph most closely resembles Mr. Wall’s earlier pictures made in what he calls the “near-documentary” mode, inspired by scenes he may have witnessed but achieved with elaborate setups and rehearsals.

Jeff Wall,Pair of Interiors, 2018. © Jeff Wall

While Wall has done multi-panel works, in that he introduces an element of temporality: read from left to right, there is an implied passage of time in which the drama unfolds. The diptychPair of Interiors(2018) continues in this mode, albeit with somewhat more subtlety. A couple is pictured in an upscale, generically furnished room. In the left frame, they are seated on a couch; the moment is highly charged, but ambiguous. In the right frame, the man is now seated on a matching chair, casting a gaze in the direction of the viewer as the woman looks askew.

In these breakthrough works, rather than an image depicting a single incident– likeParent and Child(2018), in which a man stands over a child, lying inexplicably in a fetal position in the middle of a suburban sidewalk – each panel represents oneepisodein an overarching narrative. It is no longer suspended. Something hashappened. Instead of loading the dramatic punch into one image, we have a sense of tension and release. If humans are hardwired for narrative, Wall gives us just enough information – and no more – to trigger our “storytelling” reflex, while leaving his figures so absorbed in their world, they seem to be in another one altogether.

________________________________________________

Order here:

Order here: Poster of A Sudden Gust of Wind (after Hokusai), 1993, by Jeff Wall.

The poster is printed on FSC certified, responsibly sourced paper. It measures 50 x 70 cm, including a white border and the artwork credit line, printed underneath the artwork image. Price EUR 125.- incl. Tax and shipping within Europe. Order Here!

Jeff Wall’s photograph is inspired by Katsushika Hokusai’s Travellers Caught in a Sudden breeze at Ejiri (c.1832), from The Thirty-six Views of Fuji, taken just outside Vancouver. Wall took several photographs over five months, and collaged them together digitally to create the final piece.